If my mother saw me with shoes on the rugs that fill every room of our house that day would have been the end of me. I never questioned why she’d make me take of my shoes before entering the house and I just did what I was told because I would run around the house too busy deciding which rug will give me my next adventure. See the azure rug in the corridor leading to my brother’s room was where my toys and I crashed with waves, fought with pirates, and swam with sharks to reach the shore of an island at its tethered ends. The beige one in the living under the coffee table, that I had to move every time to play on the fabrics underneath, was where I trekked the desert dunes with my action figures to reach the crystal blue oasis in the middle. Then there was my favorite rug, a solid burgundy leading up to my parent’s bedroom that sprawled the whole walkway to their door filled with perfect symmetry of all kinds and colors of flowers. This was the rug where my action figures went on the best adventure, where we created Disney influenced storylines for each flower from its colors and texture giving it heroic magical powers or poisonous evil ones that attracted my toys. This adventure never ended and I would find myself dipping and waking up from naps on this rug for years to come.

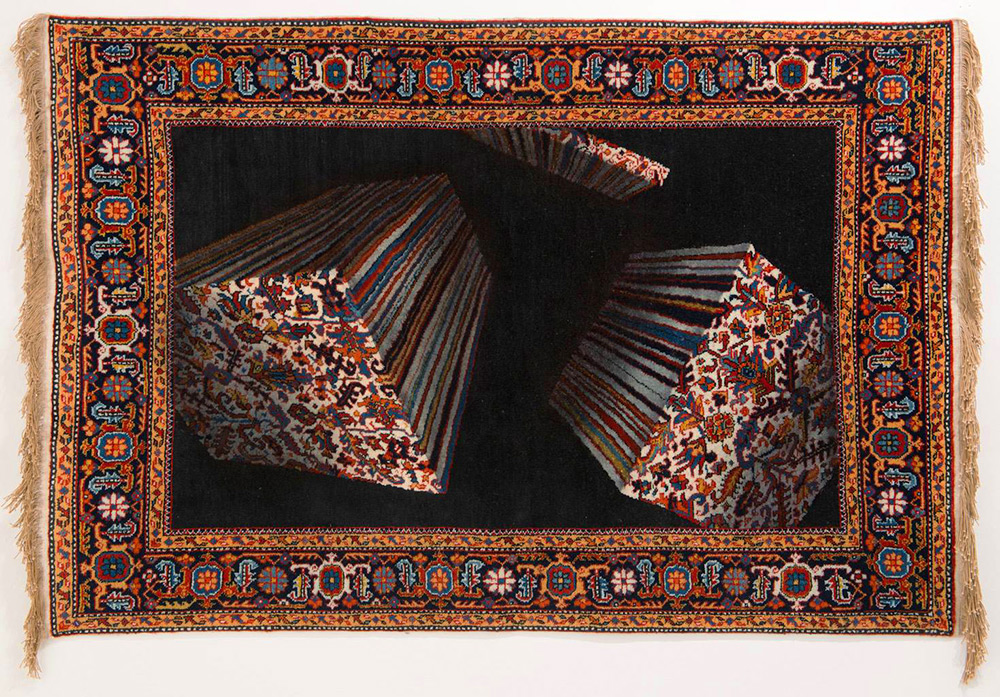

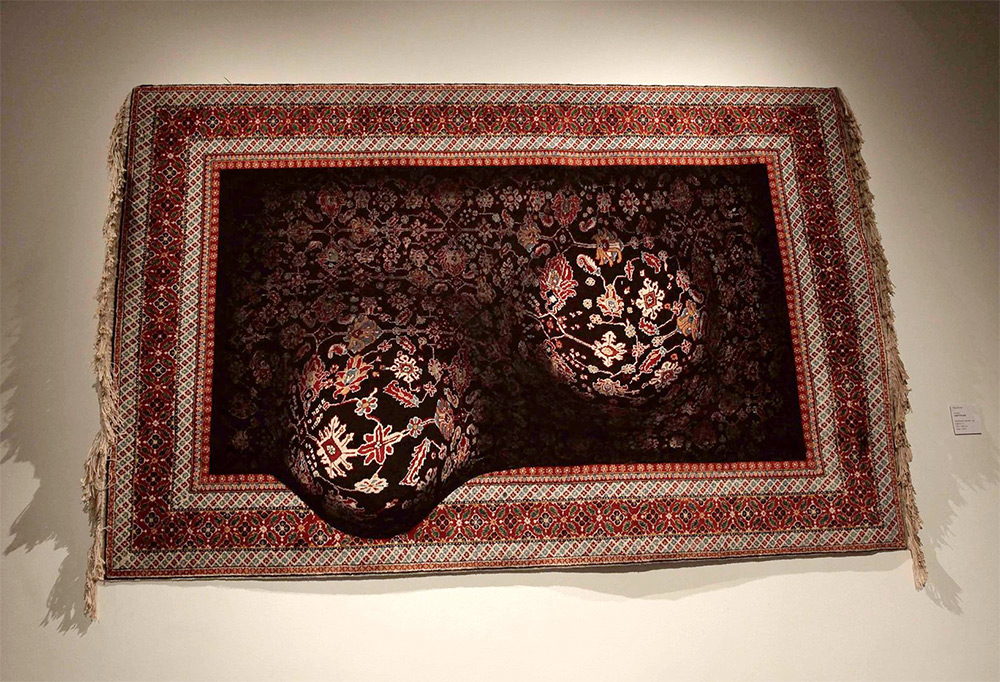

These carpets continue to hold a special place in my heart where I managed to tell my first stories through their fabrics and when I asked my mother why she tends to these carpets, even to this day, she replied with ‘they tell the stories of those that made them and, if you look closely, our story too since we have walked over them for the past twenty years.’ This is what Faig Ahmed an Azerbaijani artist is doing with carpets. He takes traditional Azerbaijani carpets un-weaves them and reconstructs them using digital patterns filled with optical illusions, glitches, and morphings to create bold sculptural art forms. In an interview he said that he is interested “in the past because it’s the most stable conception of our lives” and “Another thing that interests me is pattern,” says Ahmed. “Patterns and ornaments can be found in all cultures, sometimes similar, sometimes very different. I consider them words and phrases that can be read and translated to a language we understand.” His carpets are interplay between traditions, the stories that come with cultures and the stories we create in the present. By using fabrics, objects that have been present throughout most of mankind’s history until this very day, he draws patterns between the old and the new and more importantly connects them just as he weaves in new patterns into the traditional carpets he uses as his medium. This literal and figurative connectivity stems to a creation of great art that explores Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s quote ‘Culture does not make people. People make culture’ and the ways we think about culture, its upkeeping, and its relationship to the past.