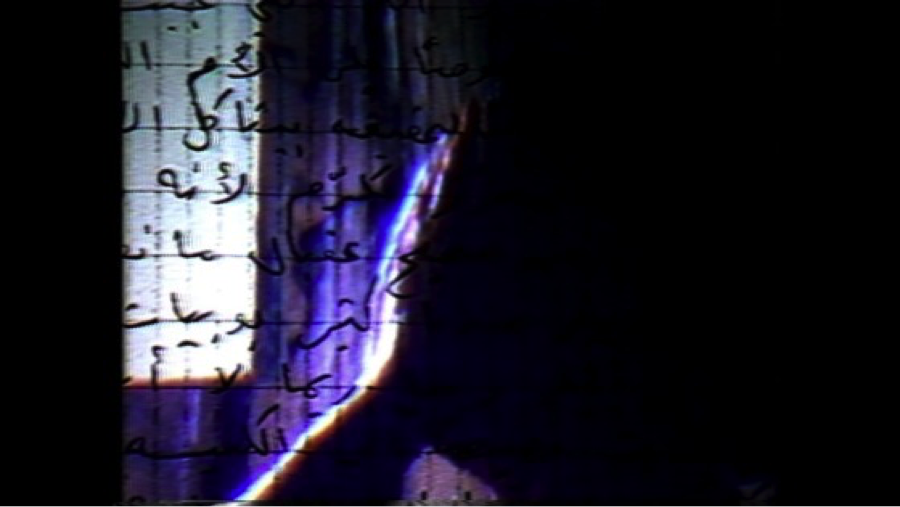

Still from 'Measures of Distance' by Mona Hatoum, 1988

When talking about contemporary Middle Eastern art, Mona Hatoum is a name always mentioned. She was born in 1952 to Palestinian parents in Beirut and a vacation in 1975 to London turned into an exile as the Lebanese civil war broke out and Hatoum decided to stay in the British capital until the chaos in Lebanon ended. The usual introductions written about her seem eager to define her and her work: a Palestinian forever in exile, early years of feminist and political activism, and a performance artist who turned to installations and exhibitions. However washing out the noisiness of the identity in her work in order to categorize and judge Hatoum by mere words is a futile process. Her complex, invasive, and multidisciplinary work, that has been at the forefront of the international art scene and has spanned over three decades, does not perform the task of classifying Hatoum into a certain category. In fact, her work does the opposite; it places you in an environment of constant flux, shows you the intricacies of an identity that is just as much influenced by her past and heritage as well as her present. One thing is for sure, that her art has a strong formidable presence and all we have to do is soak it up one work at a time.

I had the opportunity to see Measures of Distance at LACMA and I sat there watching in awe, trying to decipher the images of her mother, read the Arabic letters, and listen to the English translation of Hatoum reading them aloud; all at once. I sat there and I watched it twice and I tried and I couldn’t, with all my being, separate this piece into the entities that created it. I happened to not have left my seat after the second viewing and only when I had given up and forgotten about the inextricable layers of Measures of Distance, it started playing again for the third time. This time I watched and listened to everything and nothing. I took everything in but did not separate the layers and when I heard her mother’s opening laughter to the dialogue I couldn’t help but smile at this mess. A beautiful mess of meaning. A beautiful mess of identity that spoke of complexities of displacement and the sense of loss and separation undertaken by the individual in the social – political context of war. What Mona has beautifully weaved together was not meant to be plucked out and analyzed by separate entities; it stands on its own as a whole identity. I was plunged into the personal of Hatoum’s life regardless of how complex, contradictory, and vulnerable it is and I took it all.

With her mother’s loving voice and laughter placed against Mona’s somber tone as she reads her mother’s letters that still manage to convey tenderness and love through a war period, I was reminded of some lines from Jack Gilbert’s poem A Brief For The Defense

If we deny our happiness, resist our satisfaction,

we lessen the importance of their deprivation.

We must risk delight. We can do without pleasure,

but not delight. Not enjoyment. We must have

the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless

furnace of this world. To make injustice the only

measure of our attention is to praise the Devil.

If the locomotive of the Lord runs us down,

we should give thanks that the end had magnitude.

WATCH MEASURES OF DISTANCE PARTS 1 & 2.

Mona Hatoum Measures of Disatnce (1988) This videotape is perhaps the most touching of Mona Hatoum's artistic statement in which she examines her position as an exiled female artist. The author's voice translates letters of her mother from Arab into English, represented visually as a texture of calligraphy over the texture of her body and skin.