------

PHOTOGRAPHS:

DAWYA MOHAMED

2k16.3

I tried to fill your cup

with happiness and love

I sent good vibes your way

I sat on my knees and prayed

for you to be joyous again

I fell asleep believing that my prayers will be answered

I woke up the next hour

with a pain in my chest and no happiness

I've sent you all I've got

every last bit

your sorrow became mine

and my joy was stranded somewhere between you and me

you did not accept it

you did not return it

you kept it around just incase

you took it for granted

I learned that your cup is yours and I can't fill it

and my cup is broken and only I can fix it

------

TEXT & ART:

OMAMAH ASHMEEL

Hey friend,

I know you must feel jilted, and I apologise for that. The truth is, I have lost you and traced the parts of you in my spine to get back. You weren’t easy to lose, though. There were nights where I’d bleach you off my skin, and I’d still find amorphous hints of you in the morning. You are part and parcel of me. I swallowed your blistering sun one day when I was 7, and the white heat knocked me down only to build me right back up. It has been in my stomach ever since, hardening me for life, but keeping my warmth ever ablaze.

Although you’re situated on a large plateau in the heart of the Arabian Peninsula, you are anything but! You taught me relentless growth with your rapid industrialisation and your denizen’s habit of breeding like rabbits.

You taught me how to colour outside the lines in your city-wide canvas, spacious and stark and thirsty to absorb life. You taught me that my foundation should be strong enough to hold, like the desert, the barren surface overlays an inner brimming life that reaches depths unfathomable to the naked eye.

Your sand dunes taught me to stick to my guns, in that they withstood the test of time. They remained untainted by crass consumerism, Dutch disease, or political and religious indoctrination.

The band of grumpy drivers honking up a storm to what sounds like a crescendo street performance still reverberates ad infinitum. The smell of my mother still ripples in the ether. You’ve engulfed her body, but she sprung out through daisies. No wonder they call you the motherland. The land that mothered me, and the mother that landed beneath you.

I don't promise to keep in touch as often as I should, but I do promise to carry you like a kitschy talisman everywhere I go.

A plot for a movie that has never been made.

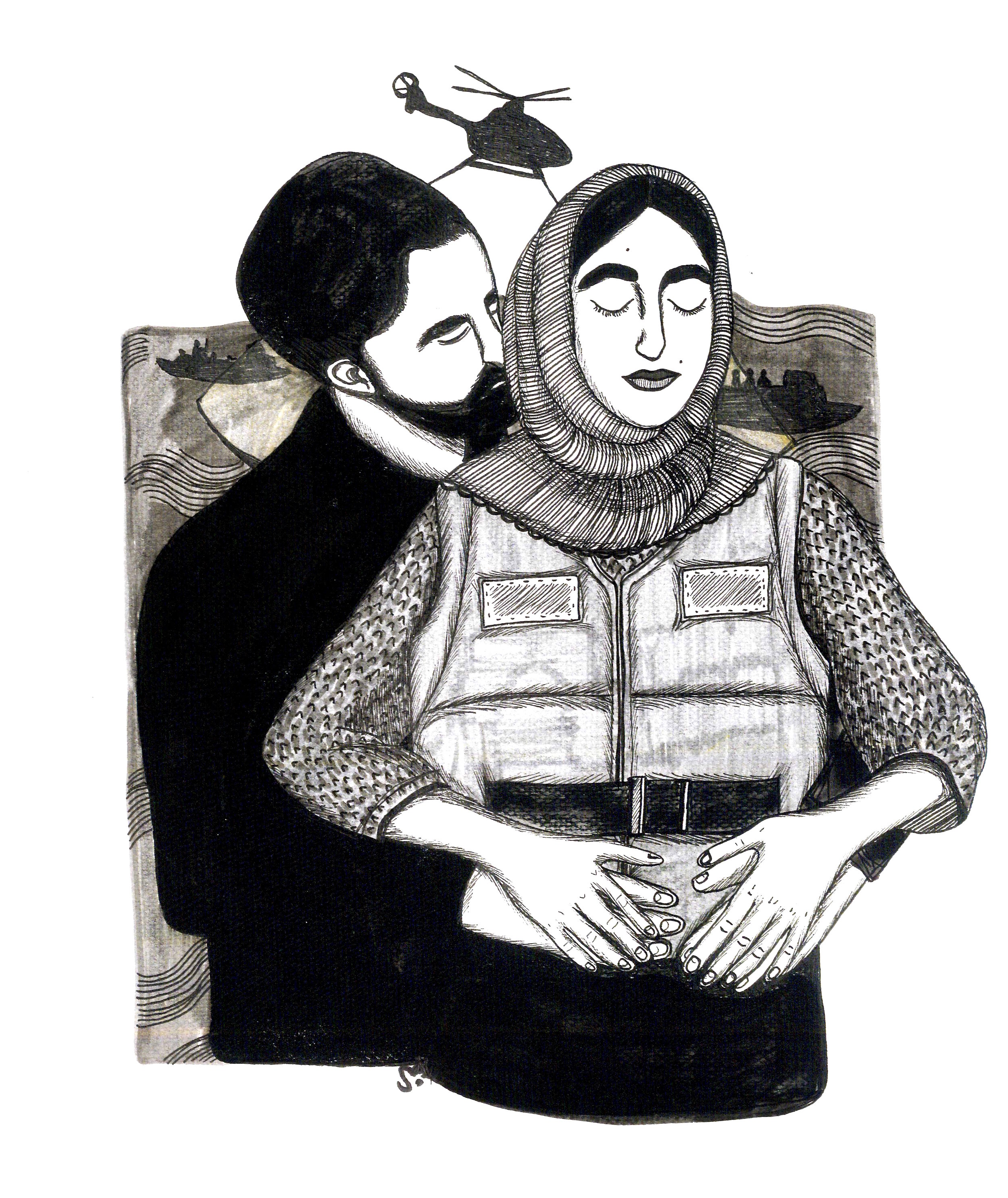

In 2015 close to the Mediterranean Sea, a young girl called Maryam Ahmadi with her fiancé Farhad Niazi and mother Reyhan board a small and grotty boat. They had left their home in Afghanistan upon the murder of her father and two brothers by the Taliban. After which, Farhad decides to bring this life of danger and constant fear to an end. Germany, where a cousin of theirs lives, started having a warmer feel and a nicer ring to their ears than their own hometown, and after selling all they owned without keeping a single thing behind, Germany became their first, and last salvation, they hoped.

They crossed the border to Iran on a bus and realized soon after that their neighbor country, although speaking the same language and adhering the same faith, wasn’t welcoming. Weeks passed and their lives kept getting worse as their residence permit status neared expiration. Throughout their stay in Iran, no time was being wasted; as making money wasn’t just means for mere subsistence, as in it they saw tickets to a better life with their basic human rights sustained in Germany. But time beat them to it, their temporary visas got expired and they stayed despite the legal prohibition of their existence. As soon as they managed, they crossed the border to Turkey. Farhad worked 15 hours a day there, and he would have worked even more if his body would not fail him every time he tried.

A human smuggler in Turkey promised them a safe and smooth passage to Greek, which would cost 5000 dollars for each, so all that work seemed just ‘temporary’. Once they cross to Europe, it will all be history soon.

At that time Reyhan, Maryam’s mother, cried a lot. She remembered her husband, his strong hands; his kind smile. She remembered how he cared for the family and their lives, working in his shop from the crack of dawn to nightfall, with true contentment and goodwill. She could not recall ever hearing him complain, or utter a single word of resentment.

As her sons got older they helped their father in the shop. Abdulrahman, their youngest, turned out to be a very talented young boy. He spoke fluent English, which he could pick up from listening to English music and movies from the market. One day he met an American soldier who asked him to translate something and later offered to pay him in return of accompanying them around to translate. He earned good money and helped the family a lot. Thanks to him the family could afford a small party for Maryam and Farhad’s engagement. But the Taliban found out about him and accused him of collaborating with the enemy.

It wasn’t long after, that they attacked the family’s home, killing everyone except Maryam and her mother who were out visiting Farhad’s family. Reyhan could never forget that day, walking back to their home; finding the bodies drenched in blood, and the pale faces of their beloved ones.

The day has come. Farhad is saying goodbye to his 15-hour job routines, now that the amount of 1500 dollars is completed and handed to the smuggler. Next station: Greece. Now they are standing in front of another grotty boat, at the small hours of night, about to board. One by one, the smuggler tells around 153 people to board the boat. Once Maryam saw the boat she knew the passage would be anything but safe.

Many people wanted to go back, but the smuggler tells them that there will be no refunds for those who turn back. Farhad says that he doesn’t care about the money, “We would find another way to get to Europe, we just haven’t looked better.” Reyhan cries and whispers that she wants to go back. She is old and she shouldn’t be so far away from home and the graves of her husband and sons. But the people behind them became hysterical while the smuggler pushed them to decide in that instant. The police could come any minute. Some people started pushing and Reyhan sinks to the ground crying.

During this moment of chaos another Afghan boy grabs Farhad’s shoulder, looks right into his eyes and says "There is no other way brother. No way back, no way fore! Otherwise we wouldn’t be here“. Maryam turns around and glances for a short moment at the other 150 people and their fearful faces. Maryam says we have no choice. Both the lower compartment and the deck become filled with people. Once the boat entered the dark sea Reyhan starts praying, repeating every line in the Quran she could remember.

Waves begin hitting the boat harshly, allowing water to creep into the boat’s surface. The captain tells everyone to throw their baggage into the sea, to cut down some of the weight. So everyone throws their last belonging into the deadly dark infinity of the sea. But still the unforgiving wind kept on viciously pushing the little boat around like it was an unwanted flea, feeding on its greatness, drowning it down with its monstrous waves that climbed onto the boat, until the Sea finally got what he desired.

The boat hit a rock, but the captain did not seem to pay much attention to it, and commanded people not to worry. But the people worry nevertheless. Some look at the black sky, black as the ocean, black like a hole. Some are screaming, some are praying. Some men are crying like little babies for their mothers, for God to help. Reyhan is horribly quiet and holds the hands of Maryam and Farhad. The water keeps coming into the boat and the captain shouts at everyone to not worry whilst clearly not believing his own words. Maryam and her family are in the lower compartment which starts to fill up with water. People move to the windows, pushing each other to leave the compartment, but it gets too tight to move and the windows are too small, and the water is coming in too fast.

Farhad pulls Maryam out of the window and then her mother and nearly before it seems impossible for him to leave the compartment, he pulls himself out. Maryam is pale, Farhad too. . They were the last ones to get out alive of the lower part of the boat. Next to Farhad there is a woman from Syria crying in Arabic for help. She can’t swim and has no life jacket. Farhad looks over to Maryam and she knows what he is about to do. He takes off his life jacket and gives it to the woman.

They swim for as long as possible and realize that they have lost Reyhan, her mother in the crowd of screaming and hysterical waddling people. Some with life jackets, and some without. Farhad was one without. After some hours Farhad looks again over to Maryam and deep into her eyes. And she knows what he is about to say. He tells her that he is too tired to swim and that he is going to float on his back and rest. For a moment Maryam is turning her back to him looking desperately for her mother. But it is too dark and she can’t see. T

he waves are high. Suddenly she realizes that he floated away. She can hear him calling her, but he gets further and further away. Time passes. Maryam is freezing. Eventually a boat finds her. But they never find her husband Farhad or her mother Reyhan.

------

TEXT & ART:

MOSHTARI HILAL

------

PHOTOGRAPHY: CHEB MOHA

This morning I woke up and found the snakeskin

of yesterday strewn about me.

This morning I woke up anew.

Mornings have always been favorites of mine,

I am blessed to be able to open my eyes

with amnesia

at whatever chaos the night before contained,

whatever I let myself believe in the dark.

I fall asleep and dream of she in the morning

she who wakes up with sunshine in her mouth

teeth bursting bright white sunbeams, I

make it a point to smile at myself in the mirror

because that she is me

and she’s one to smile at herself in the mirror.

This was always who I was.

The kind for

fresh starts and

startovers,

new beginnings and

resolutions.

I have always been infatuated with evolution.

I make it routine to

close my eyes and drag my hands

over the masterpiece that I am.

I am creator looking for imperfections,

wounds left to lick, I am

prodding for

places left to heal

places left to patch

places where love can grow

like flowers in cracked city pavement.

I have always been in lust with change.

I make it routine to

peel layers back

till the core of who I am

is in image of the Earth herself,

magma hot and

untouchable. Unreachable.

I have always been bewitched with revolution.

People tell me that I’m different now,

they ask me where “all of this” came from,

where it was growing up

I tell them it was not.

It was yet to be.

People tell me I’ve got a temper,

but I shed that skin years ago

from my mind before my body, I am

still picking at the wound that blazed when I let it go.

People tell me I’m not one to keep a grudge

but that was when I let the world walk right over me.

I am a doormat that grew legs and feet.

Don’t expect me to accept it when you

expect me to be the same person you made up your mind that I am.

Don’t expect me to stay the same.

I am crystal in chrysalis, I am

phoenix set on fire, I am

half coal and yet half diamond, I am

the sculpture and the sculptor, I am

creator and creation, I am

both poet and the poem

I’m crossing lines to cross out lines

writing notes in margins

that end up whole verses themselves

re-reading, reciting, editing, I am

rising from the dust and clay -

growing.

Give me the space to.

This is not a request, it’s a demand of you. I demand to

capital B

Become.

full stop

------

TEXT: RAWA MAJDI

THUMBNAIL ART:

SARAH ALHUSSINAN

Grief |al- huzn الحُزْنُ

/ɡrēf/noun

eep sorrow, especially that caused by someone's death.

“I will never stop grieving Bailey because I will never stop loving her.” -Jandy Nelson, The Sky is Everywhere

See also: Love/hubb حب

Funeral Homes بيوت العزا

**Funeral homes have distinct smells. They smell like the bitter mixture of ground cardamom and roasted coffee beans, boiled in water and set so the grounded spices and coffee could settle before being served. Jiddo’s funeral was the second home I had been to where the deceased was actually somehow related to me. Somehow the grief of the family fit into the small cups, but was too big for the house. Somehow the small cups withstood the pain, but the carpets greyed, the walls peeled, the circuits were shorted. Funeral homes felt like the pain in my lower back from bending to offer the hundreds of guests dates from the heavy crystal dishes my aunt set aside for us. Funeral homes smelled like ground coffee and tasted like dates.

Mamma, your teta, was upset when I told her I would call this letter byut al-'azza—she thinks I’m being too depressing. But byut al-‘aza stopped being “depressing” for me when her grandfather died. They started feeling like home and the last thing I had left of him.

This Wednesday, the 26th of October, marks the two year anniversary of jiddo, your great grandfather’s, death.

Jiddo used to sleep every night at 10:30, with two exceptions: the first day we arrive from the States or the last day before we have to go back. We had been in back in the states for two months, and your grandmother had spent the entire month of October worried--with this overwhelming feeling that she had to go back. Maybe the things destined for us, because they exist in ‘ālam al-ghayb and outside of the realm of time, are always pulling on us as we continue living, so that the closer we get in time, the stronger that pull becomes. And maybe the homeland is always calling her children from the diaspora.

Some hours after jiddo went in to his bedroom, he was woken up by loud screaming and the screeching of tires and a car and house being set on fire. He went outside, despite protests from the son that lived with them and teta, your great grandmother, and the expected how could you go outside in your pajamas? This was a man who only rarely got angry, but who could not sleep through an opportunity to help. Two of his nephews, he discovered, were in a fight with one of the neighbors and his son.

Jiddo walked out, without his cane, without his shmagh or his ‘abaah, onto the street lit only by one lamp. His nephew did not see him, and as he sped down the hill, he hit jiddo. He flew into a pole. It was death on impact.

…

My darling girl, every ibtila’ after this one was negligible. I knew it would be like this. When khalto Sakha’, your grandmother’s sister, told us, she did it in pieces. She told me he was sick first. Then that he went into a coma. I remember it so vividly. I was on the floor mattress in my bedroom, and I was reading her messages, and I put the phone down, and I begged God to not test me with his death. God, I told him, I know he has to die eventually, just not now. Please don’t do this now. Please don’t test me like this. Not now. And then she told me to tell my mother to call her. He was “in a coma” for an hour before my aunt told us, in a message that seemed to hold all the finality in existence, “Lulu, your grandfather is in the gardens of eternity. And to God we belong and to Him we return.”

…

We came like guests to my grandparent’s home, aboard the first flight available from JFK, we arrived at the end of the first day people were coming to give their condolences.

When he wasn’t there to greet us, but other women in long and dark colored jalabīb were, I knew the house was transformed from beit il-eilih to beit ‘aza. It used to be the family house, but now, it was just a home of the deceased. Still, it was a home. A home that would come to hold the grief of our broken hearts. My darling girl, it was the moment that this house transformed into a beit ‘azza that I came to feel at home in homes where people were being mourned and others were coming to offer their condolences. And it was the moment that I felt might be captioned with that unspoken but certain condition of living in the mahjar:

"لما تعيشوا في الغربة لازم تتقبلوا فكرة انه ممكن يموتوا وانتو مو هون"

But that at least meant you had some valid grief—even if it meant you signed away your right to mourn properly or say goodbye to the deceased before they buried him because well, we can’t delay. But we can’t delay sounds too much like your grief is less important for me to hear it any other way.

I don’t know yet, sweetie, where I’ve brought you up, and I don’t know where we all live, whether it’s with our family, or if everyone is on their own, and I don’t know how lonely you may feel, or if, even if we live together, you sometimes feel like you live in some sort of diaspora or that your claim to loving someone or something you don’t live with is challenged or tested.

…

When I got ready to leave to the airport with her, mamma asked me why I was going. Her question made me feel like I was on borrowed grief. It reminded me of every time I told her I wanted to move to Jordan and she said “You’ll get tired of it, you’ve lived your whole life here, you couldn’t possibly.” I felt like my mother was doing to me what everyone else there did to her.

Here is unspoken but certain condition of living in the diaspora #2: to everyone else back home, you are simply less—less attached, less genuine, less true to your roots, less loving, less bereft, with less right to mourn. Because even when we arrived, after all the people left our house around 11, and before they came the next day at 9am, and after they left again at 11—throughout that entire week I was there, everyone made me feel like my grief was borrowed and that it was second to their own, to the grief of someone who lives in Jordan, someone who has not moved away.

My sweet girl, in those days grief felt like a competition I was bound to lose.

They all told stories, about what happened when they first heard, how they reacted, how happy and peaceful he looked, they all posted these super sentimental Facebook elegies (and I was the writer), started thinking of different ways for his children (not grandchildren) to give charity on his behalf (passing out meat, money, books, paying for water pumps, etc.). They were all very expressive. I said nothing, because my story felt irrelevant. My aunt told the story of how my cousin found out—over and over again, and every time it felt like everyone who listened was nodding away my right to grieve. I cried, and I sobbed, and I heaved, but mostly I acted like I always did. So it felt like they only saw the lack of expression, and the ordinary smiles and laughs, and I heard in it all she’s only his granddaughter, and she doesn’t even live here.

I could not begin to heal. My grief felt so unearned and unworthy—so second to everyone else’s. I was not unused to this feeling, but I’m only making the connection now as I rewrite this letter for the third time to you, and after some distance. When jiddo died, I had just gotten out of a marriage I had spent two years in where I constantly felt like my emotions were second to his, that he probably had it worse and telling myself to see it from his point of view, that he was depressed and there is nothing wrong with you, suck it up. In retrospect, I think a lot of my feelings about how much less valid my grief was had to do with this.

So I stayed quiet and I grieved politely, as I expected I could without bothering anyone else, without making them feel like I wanted to win the competition, that I was doing anything but respecting the pain I must gracefully admit is more than my own. When I returned in April without my mother, and everyone’s pain had eased into a daily sort of mourning I could not upset with my own, I cried every night. For three weeks, when everyone slept, I blew my nose into napkins, wiped tears on the sleeves of the black hoodie I wore to bed, sat on his bed and talked to his pillow, and memorized the tiles on the bathroom wall through red and stuffy eyes.

…

I am writing this letter to you, my dear, because I want you to know that Grief is never a competition. Just because someone has it “worse,” that doesn’t mean that you’re okay, and you don’t have to be. And just because you may live away from the people that you love, it doesn’t mean that you love them any less, or that you would grieve at their passing any less. And just because we grieve in these different ways, and in different times, none of our grief is invalid or less.

My love, this is not a letter where I tell you never to move or visit new places because someone very close to you might die and you may never see her again. This is a letter where I tell you that everyone will grieve differently—and some of us without knowing that we grieve. And to tell you that when we break—the cracks along which we separate and shatter are different for each of us.

We may never be unbroken. But I will be with you when you break, and when you begin to heal, and ya rabb too when we’re in that place where we can’t ever break or fear or grieve again.

I love you,

R.

October 22nd 2016

------

TEXT: R. K.

THUMBNAIL PHOTOGRAPH:

MESHARI BIN HASSAN

------

ART: REEMA MOTIB

I have never stayed in one place for more than nine months. One hundred and sixty-six visa stamps between Lebanon and the UAE. That is eighty three trips in total turning into an average of a three months stay at one place before leaving. Looking at a map I was not able to pinpoint home as a location, instead my meaning, as well as most kids who grew up between multiple locations, of home transcends location and turns into an experience of home rather than a tangible structure or place. Mapping Home is my experience of finding home by weaving the tangible with the intangible using everyday objects like maps, threads, needles, and tokens collected throughout my life. In this piece, as I repeated the motion of stitching threads through a map, the locations themselves faltered into voids giving the threads a predominant location of a map that wasn’t accustomed for them. As the holes thickened and there was not enough space to weave through the two countries, the previous threads, my previous journeys, gave support to the threads to come as I started weaving through the line of wool itself and not the map. All the while the back end of the map was left to organically weave itself through and through creating a secondary mapping, a map that more accurately describes the terms of what a home means to me; tangled lines, relations, some taut, some loose yet all contained in one space, in the thread of wool, in my experience of living.

FIRST TRAVEL BETWEEN ABU DHABI AND BEIRUT IN 1995

TRAVELS BETWEEN 1994 (YEAR I WAS BORN) AND 1997

TRAVELS UNTIL 2005

TRAVELS UNTIL 2016

------

ART:

NADIM CHOUFI

LEBANON

Sobh bekheir,

I just woke up, thought I’d write you a couple lines. How are you feeling today? What are you doing all day?

In all my dreams, I run back to you, we meet again in our arms, we meet again at the sea, we meet again in the sky.

Delam barat tang shodeh, I miss your perfume, the taste of your lips, the softness of your fingers caressing each square of my body, my skin shivering,

I need you like I need air.

As soon as I am back, I’ll ask you something very important…

PS: I forgot to tell you, I found a beautiful green djellaba at the souk, I bought it for you. I know green is your favourite colour.

Asheghetam,

Bedrood.